That’s it. That’s the advice. Don’t buy superwash. It’s bad for the environment, it’s bad for people living near the plants that scour and superwash wool.

- Introduction

- The first superwash treatment: chlorination

- Chlorination and the structure of the wool fibre

- Research on chlorination

- References

Introduction

In part 1, I told you why I feel the duty to speak out the truth about the disastrous ecological impact of superwashing wool and why I am in the fortunate position of not having any conflicts of interests. Let me stress here that I am not writing these posts as an attack to all the small businesses that I trying to make a living out of their passion for wool and knitting. If these posts are to be viewed as a wake up call – and I hope many will read them as such – this wake up call is primarily aimed at the big yarn companies, aka the ones that are in a position that allows them to decide whether or not to superwash their wool and if yes, with which process. But not only.

My wish is for wool consumers to change their purchasing in favour of non superwash wool. Because even in our actual situation, most of our cherished local yarn shops and small businesses do in fact carry non superwash wool. The same goes for online yarn retailers. So the more we individual knitters buy non superwash wool, the more increased demand for non superwash wool there is, the more wool producers will supply us with such wool. As the saying goes, don’t curse the darkness, light a candle.

The first superwash treatment: chlorination

The superwash process is a 20th-century invention with the purpose of treating wool to prevent it from shrinking and felting, as it naturally would when laundered in a washing machine. For centuries, sheep were primarily raised for their wool, not their meat, as there was significant profit to be made from selling wool. However, in the 20th century, the price of wool experienced a significant dip in the 1930s, partly due to competition from synthetic fibers for the first time. World War II brought a temporary boost to the wool industry due to high demand for items like uniforms and blankets

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the wool industry was flourishing as the textile industries in Japan, France, Italy, and Germany began to grow again. However, things took a turn for the worse in the late 1950s when the second generation of synthetic fibers, such as nylon, polyester, and acrylic, entered the market and started eroding the market share of woollen garments. By the 1970s, the price of wool had hit a very low point. Yet, the wool industry was not ready to relinquish its market share in the textile industry without a fight.

Their strategy was twofold: 1) to promote the Woolmark logo as a certification for 100% woollen garments, and 2) to make massive investments in industrial research to create more “convenient” woollen garments that wouldn’t irreversibly shrink and felt when laundered in washing machines. By the 1960s, individual washing machines were already widespread in the Western world, and woollen garments, which still had to be washed by hand, were struggling to fit into this modernity. What was needed was a new type of wool, one that was convenient and easy to wash. Or so was the prevailing mindset at the time. A new wool was required, and not only that, customers needed to remember how easy and convenient it was to wash this wool. This is how “superwash” came into existence, for better or for worse. I will argue that it was, and still is, for the worse.

Chlorination and the structure of the wool fibre

The first efforts to create a superwash wool had occured in the 1930s. The process used for shrinkproofing wool was chlorination, which typically involved immersing the wool fibres in a chlorine gas or liquid chlorine solution.However, this process was so harsh on the fibres that the wool would often broke during spinning. Before delving into an explanation of the results of hese first wool treatments, it’s essential to take a closer look at the composition of sheep’s fleece, the structure of wool fibres and the mechanisms responsible for felting. This will allow us to better understand the impact of the chlorination process as well as getting a better grasp of its similarites with its contemporary counterpart, that is the chlorination/Hercosett treatment.

(This is going to be a rather lengthy explanation, but bear with me, as I will be providing you with knowledge that will allow you to make your own informed choices when sourcing your yarn supply.)

The fleece of sheep

All fibers originates in the skin of the sheep, from the follicules located in the epidermis. The follicules can produce three types of fibres : hair fiber, kemp fiber and wool fibre. Some sheep breeds only produce hair fibres or mostly hair fibres. A typical example of such a breed is the Bapedi sheep. Hair sheep can be reared for their skin (leather) and meat, but not wool. These sheep are called hair sheep.

Sheep breeds described as “wool sheep” produce a fleece made of hair fiber, kemp fiber and wool fibre. The higher the percentage of kemp and hair fiber, the coarser the wool. Hair fibers are inelastic and tend to be sleeker, straighter, wavy rather than crimpy. Kemp is the heaviest and coarsest of all hair fibers and they tends to be short, stiff and brittle .Wool fibre are finner, softer, elastic and crimpy rather than crimpy. How much crimp the wool fibres have varies amongst the sheep breeds. Similarly, the amount of kemp in the fleece differs from sheep breed to sheep breed, but can also change throughout the year. An example of a sheep breed whose fleece has a hight percentage of kemp is the North Ronaldsay. On the other end of the spectrum is the Merino sheep, whose fleece is almost kemp-free.

The wool fibre structure

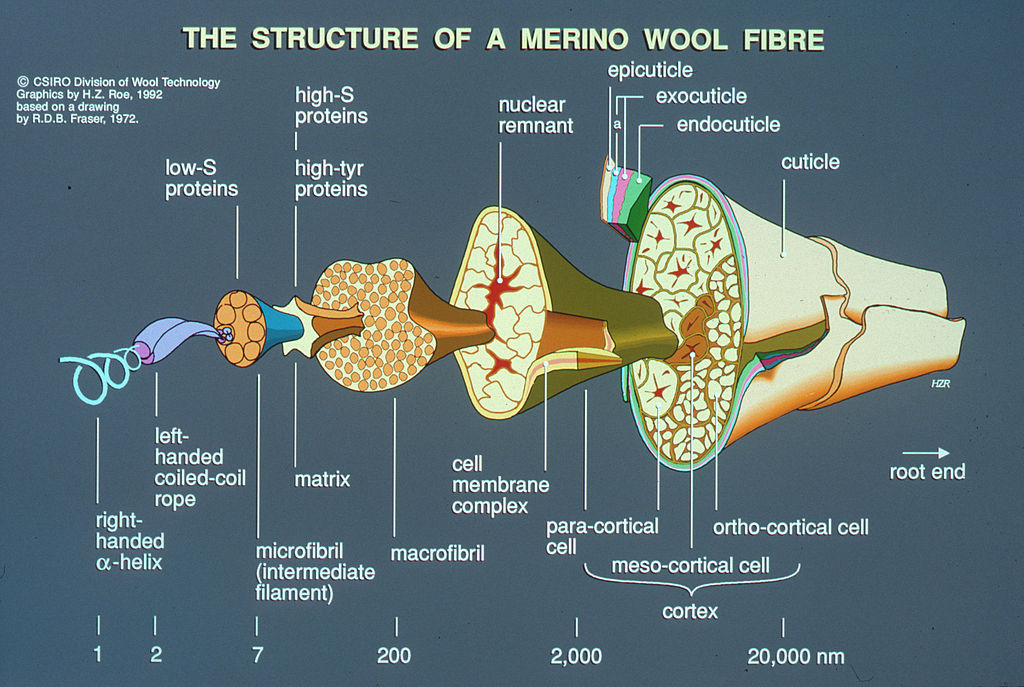

As this schematic shows, the structure of wool fibre is intricate. You will find here a detailed explanation of its different compounds. Yet for our purpose of understanding the chlorination process, we only need to focus on two key components : the outer layer, known as the cuticle, and the core of the fiber, called the cortex, with their distinct properties. The cuticle, the outer layer of a wool fiber, consists of overlapping scales, or cuticle cells, making it hydrophobic—resistant to water. This is why water droplets tend to bead up on the surface of wool. In contrast, the cortex, the largest part of the fiber, is hydrophilic, meaning it readily absorbs water and is primarily composed of the protein keratin. The schematic provided represents the structure of merino wool fiber, but all wool fibers from sheep share this fundamental characteristic: an outer layer with hydrophobic overlapping scales and a hydrophilic cortex.

This combination of characteristics offers significant benefits to the sheep. The hydrophobic scales act as a natural barrier, protecting the wool fiber and the animal’s skin from rapid saturation when exposed to external moisture, such as rain or dew. Simultaneously, the hydrophilic cortex can absorb moisture, such as sweat or condensation, and effectively distribute it throughout the wool fiber. This moisture absorption aids in cooling the animal in hot weather by wicking sweat away from its skin. During colder conditions, the absorbed moisture within the wool provides insulation by releasing heat as it evaporates, thereby helping the animal maintain its body temperature.

In knitted garments too, the interplay between the hydrophobic scales and the hydrophilic cortex is what creates its unique qualities.

The scales play an important role in providing stability and resistance to deformation. When the fiber is subjected to stretching or deformation, these scales act as a kind of “locking mechanism.” They resist the stretching forces, helping to hold the fiber’s shape and structure. When the stretching force is released, the interlocked scales assist the fiber in returning to its original state. This property is known as elastic recovery and is a key aspect of wool’s natural elasticity. Wool’s natural elasticity allows it to stretch and then bounce back, making it resilient and capable of maintaining its shape even after being subjected to stress or deformation.

When we block a knitted item, we are intervening on relaxation shrinkage. Relaxation shrinkage is the type of shrinkage that occurs when wool fibers return to their natural state after being stretched or distorted. When we block an item, we manipulate the wet fibers to achieve the desired size and we then pin it on a flat surface so that it dries while maintaining its new shape. The drying process sets the wool fibers in their newly relaxed state, essentially “locking in” the shape we have created through blocking. We are using the wool’s natural elasticity and ability to bounce back, but controlling it to bounce back to the dimensions we see fit.

Furthermore, woolen garments provide us with excellent insulation. The hydrophilic cortex, the core of the wool fibre, absorbs and distributes moisture away from our body when we sweat or when the environment is humid. As this moisture evaporates, it releases heat, helping to cool us down in warm weather. Conversely, in colder conditions, the absorbed moisture in the wool can provide insulation by trapping heat and keeping us warm. Like the sheep, we are benefiting from wool’s unique combined fibre structure.

However, it’s precisely this remarkable fibre structure that presents challenges when it comes to washing and dyeing wool.

Felt

Wool + agitation + heat = felt. And what happens when you launder your knits in your machine-washing ? Agitation and heat, which is why your knit comes out in a pitiful state, shrinked to the stage of unwearability and matted. In short, your knit was on its way to become felt, but usually your washing program’s heat was not warm enough or not long enough for it to become real felt. So there it is,, totally useless and the worse is : there is nothing you can do to reverse the process. Felting shrinking is irreversible. (My suggestion : go full felting, put the item back into the washing-machine, high heat and long washing program , use the fabric thus created for homesewn slippers, inside soles or a small bag for your child).

When trying to create your own home-dyed wool, you are facing the same conendrum: you need a hot dye bath for the wool to take the dye, but you also need to disperse the dye without agitating the water or the wool or both as this will cause irreversible felting.

In short, wool is not convenient to wash and is not convenient to dye. You could even end up felting your knitted garment through hand washing if you don’t wash it carefully! Synthetic fabrics, on the other hand, are very convenient. They take dyes beautifully and don’t start felting when washed. Why the difference?

The difference lies in the structure of the wool fibre and its physics. The outer layer of scales all point in the same direction. So when agitated in water, with some pressure put on them “the individual fibres move preferentially in one direction, become entangled and consolidating the structure of the assembly (Allen, 1993, p. 72, citing Makinson, 1979). ” and “as the fibres become entangled, they pull themselves closer and closer together, increasing the density of the mass of wool. In other words, they become matted and cannot be separated out again (ibidem)” (aka they become felt). All the tangled fibres have compacted into a dense, interlocked mass. Contrary to what happens in relaxation shrinkage, the entangle fibers, now tightly interwoven, have lost their individual freedom of movement. The fabric thus created is both rigid and inflexible. There is no “bouncing back”, no “blocking into a new shape” possibility. Felt shrinking is due to the extensive entanglement of the wool fibres and the result of this process is a consolidated, thicker and shrunken wool fabric. Alas!

Research on chlorination

As explained above, irreversible shrinking and felting are one and the same process. It is this felt shrinking that has been the target of the superwash process from the very beginning. The aim was to make wool more “convenient” for the end customer, but also more “convenient” for the yarn manufacturer. One of the goals being to have a wool that would be easier to dye. Finding such wool treatments were especially important for merino wool. As Allen reminds us:”The finer the wool, the more rapidly it will felt (Allen, 1993, p. 72)”. Merino wool being one the finest wool that exists, it is especially prone to felting. An information you don’t often come across, do you?

Australia, New Zealand and South Africa were mostly raising merino sheep (and continue to do so to a large extent). They promoted their shared interests through the International Wool Secretariat (IWS) which funded both promotion and research. An important research center for the wool industry was the Australian based Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) that worked in tight connection with Australian manufacturers. This institute played a major role in the efforts to develop a superwash wool treatment. The discovery of the Hercosett process in the early 1960s is credited to them, and it remains the most widely used wool treatment to this day. The Hercosett process consists of two steps: 1) chlorination and 2) coating the wool fibers with a polyamide-epichlorohydrin resin. When wool is labeled as ‘superwash,’ it almost always means that the wool has undergone the Hercosett process treatment.

The Hercosett process’s discovery was made possible by earlier studies that focused solely on the chlorination of wool. Researchers conducting the studies did not term it ‘superwash’; instead, they referred to it as ‘shrinkproofing’ wool. Chlorination involves immersing wool fibers in chlorine gas or a liquid chlorine solution. Initial studies aimed to describe the effects of chlorination on wool and understand why and how this treatment was effective in preventing felt shrinkage. However, it was discovered that while chlorination was effective in preventing felt shrinking, it was harsh on the wool fiber, completely destroying the outer scales and sometimes damaging the cortex of the wool. Despite this, manufacturers welcomed the technique because it was cheap and effective at preventing felting. Over the years, the technique was refined to improve the uniformity of chlorination, as any untreated fibers could still create felting. The wool, however, remained prone to breakage.

The discovery of the Hercosett process marked a significant breakthrough in the wool industry. Unlike previous methods that treated chlorination as the primary process, the Hercosett approach positioned chlorination as a preliminary treatment, employing a more controlled application of chlorine. This measured approach ensures that the outer scales of the wool fibers are softened without causing extensive damage. The application of a coating prevents scale entanglement, resulting in a smoother fiber surface that is very soft to the touch. In comparison to earlier chlorination treatments, the Hercosett method represents an attempt to achieve a trade-off: preventing felt shrinkage while minimizing damage to the wool structure. Wool treated with the Hercosett process is thus less prone to breakage than in the earlier chlorination processes.

And yet, there’s a significant hitch – the Hercosett process still relies on chlorination. And this is a big problem. The use of chlorination in the Hercosett process, while effective in delivering machine-friendly knits, isn’t just about transforming the properties of our wool. It’s also leaving an impact on the world around us. Simply put, the Hercosett process is not environmentally friendly. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. And a substantial part of this environmental issue stems from its reliance on the chlorination process.

Chlorination is not only used to treat wool. In swimming-pools, chlorine is added to the water to desinfected it. Despite the levels used being much lower than those used in the chlorination of wool, there has been quite a few concerns about the safety of this procedure for swimmers and people working at swimming-pools. The hazards come from the byproducts that can be generated through the interaction of compounds in the water. Similarly, chlorination in wool treatment is known to result in various toxic byproducts, harmful to human health as well as the environment .Unfortunately, our knitting choices, even when made with the best intentions, can unintentionally contribute to a larger environmental challenge. It’s been a painful realisation to me. Here again, let me stress that I am not writing these posts to patronise or blame anyone. I am writing because I am passionate about knitting and passionate about us making informed choices. My wish is to empower the knitting community. By unveiling the so-often overlooked ecological cost superwash wool, we can urge the wool industry to inform us of the wool treatments they are using, increase the demand for non-superwash wool, etc. In short, we can make choices that align with our values.

Therefore we will explore the toxicity of the chlorination of wool in part III, as well as the environmental downsides of the Hercosett process in general. In part IV, we shall explore the different alternatives to the Hercosett process that have been developed but are still not widely used by the yarn industry.

3 thoughts on “Knitting Advice Nr. 11: Don’t buy superwash wool (Part 2)”