That’s it. That’s the advice. Don’t buy superwash. It’s bad for the environment, it’s bad for people living near the plants that scour and superwash wool. This post is part of a serie of posts where I give you a detailed account of what superwash wool is , how it is created and what are its global impacts. In this part, we are focusing on the ethical and environmental downsides of the chlorination of wool, the first step of the Hercosett process.

- Introduction

- Toxicity of chlorination

- Toxic byproducts of wool chlorination: persistent organic pollutants (POPs)

- Adsorbable Organic Halides (AOX): measuring the scale of the disaster

- Superwash and the pollution haven hypothesis: examining China’s role in the global wool industry

- Flabbergasted

- Next

- References

Introduction

In part 1, I told you why I feel the duty to speak out the truth about the disastrous ecological impact of superwashing wool. I also told you how I am in the fortunate position of not having any conflicts of interests, free to speak out.

In part II, I provided you with some insight into the historical context of the superwash wool revolution : a response by the wool industry to its loss of market shares to synthetic fibers, starting from the mid-20th century. A twofold response : 1) the creation of the woolmark trademark, 2) research in the desperate effort to make wool as “convenient” as synthetic fibres, aka machine-washable. The first wool treatment applied and thoroughly studied was the chlorination. This method did prevent felting but came at a significant cost—making the wool very fragile. Then, in the early 1960s, chlorine became a pre-treatment of wool before being coated with a resin. This process, called the Hercosett process, was marketed as producing “superwash” wool. This wool treatment is still in wide use. Indeed, to this day, it is estimated that around 70% of all wool labeled as fully machine-washable is treated by the chlorine-Hercosett process.

In this part, we are focusing on the environmental downsides of the chlorination of wool. This is not the only part of the Hercosett process that rises very high ethical and environmental concerns, but for the clarity of this exploration, I have decided to split this content into several parts. We are therefore going to follow almost the enterity of the life cycle of superwash wool, namely 1) the chlorination of the wool 2) de dechlorination of the wool 3) the application of the resin coating 4) the sheding of microplastics 5) biodegradability. In further posts, we shall be discussing the alternatives to the Hercosett process that already exist. For those of you who are not willing to read such an extensive content, I will be providing you with a very condensed version of this serie of posts in January. I am writing theses posts as I am doing my research, and yes, it is taking me quite some time. Please bear with me. Meanwhile, let me already tell you that one of the ways of being sure you are not buying superwash wool treated with the traditional pre-chlorination/Hercosett process is by purchasing wool that is GOTS-certified.

Before we dig in, let me add a little caveat and a call to my readers. I am providing this content in all honesty and to the best of my ability. Please keep in mind that I am not a chemist, a physicist, a biologist, etc. I am just a knitter. I do have a free access to a wealth of scientific literature, but that doesn’t mean I understand it fully. This post about the environmental damage caused by the chlorination of “superwash wool” is only as detailed as what I have managed to grasp from the articles I read.

Fortunately, the introductions and conclusions of such articles are often in plain English. Therefore I am 100% certain that the Hercosett is toxic for the environment. This toxicity has been at the heart of past and present researches to create a more environmentally-friendly wool treatment. This toxicity is thus openly discussed in the field’s professional literature.

I have listed most (but not all) the references I have used to document this post. Let me stress that all articles written in this century all highlight the fact that the chlorination of wool comes with very significant environmental concerns. The debate surrounding wool chlorination no longer centers on its environmental impact but rather focuses on identifying the most effective and sustainable alternatives. The scientific consensus is unequivocal: wool chlorination poses significant environmental risks.

If you readers should come across a factual mistake in this post or feel I have neglected an important aspect of our topic, please let me know in the comment section. I would be very glad to collaborate with you to update this post accordingly.

Toxicity of chlorination

Chemical properties of chlorine

Chlorination involves treating the wool with chlorine or a chlorine-containing compound. Chlorine is a chemical element; it has symbol Cl and atomic number 17. Chlorine is an extremely reactive element. In plain English, chlorine is like an extra-friendly person, keen to make as many friends as possible and in all circumstances. Chlorine has the highest electron affinity and the third-highest electronegativity behind only oxygen and fluorine. Chlorine is what chemists refer to as an halogen. In plain English, this means chlorine forms very strong bonds with its friends—so strong that it could be described as being very clingy and unwilling to let go of anyone. Chemical bonds are formed based on the sharing or transfer of electrons between atoms, and the strength of these bonds is determined by various factors, including electronegativity. Describing chlorine as clingy is of course an oversimplification, but for our purpose, all we need to understand is that chlorine makes strong and stable bonds.

What happens when wool comes into contact with chlorine

The main chemical elements found in wool are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur. Chlorination involves a chemical reaction between chlorine and the sulfur element naturally present in wool.

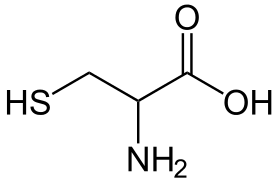

Wool is primarily made up of proteins, and proteins are intricate molecules constructed from smaller units called amino acids. Cysteine is one such amino acid present in the protein structure of wool. What sets cysteine apart is the presence of a sulfanyl group (-SH), which contains sulfur. When chlorine is introduced to wool during chlorination, chlorine atoms bond with the hydrogen atoms in the sulfanyl groups of cysteine, resulting in the substitution of hydrogen with chlorine. This process is a form of oxidation, that is a reaction where substances lose electrons. In simpler terms, the chlorine is essentially replacing certain hydrogen elements in the wool structure.

structure of wool. Notice the sulfanyl group (HS) on the left of the picture.

Now, the oxidation of the sulfanyl groups of cystein is crucial because it leads to the formation of disulfide bonds within the wool’s protein structure. Disulfide bonds involve the connection of two sulfur atoms, creating a stable link known as (-S-S-). The deliberate formation of these disulfide bonds is the primary objective of the pre-chlorination process Because these bonds change the overall strength and resilience of the wool fibers. The cross-linking provided by disulfide bonds results in a more durable structure, making the wool less susceptible to the typical factors that cause shrinkage and felting, such as mechanical agitation and changes in temperature.

Unfortunately, the creation of disulfide bonds is not the only thing that happens when wool fibres get into contact with chlorine. As stated earlier, chlorine is a very reactive element. It is also a strong oxidising element. Which means chlorine readily participates in chemical reactions, particularly with organic compounds like those found in wool. Remember what we said about chlorine being extra-friendly and looking out for new friends all the time and everywhere ?

As chlorine reacts with the wool fibers, it can break certain chemical bonds within the protein structure. This breaking of bonds is an oxidative process, involving the removal of electrons from the wool molecules. In the chlorination process, chlorine seeks to achieve a more stable state by accepting electrons from other elements. The specific reactions depend on the nature of the amino acids and functional groups present in the wool. In other words, alongside the creation of disulfide bonds, chlorination results in the formation of unintended byproducts.

Currently, the prechlorination of wool in the Hercosett process requires 0.5 ton of chlorine for the treatment of one ton of wool.

Toxic byproducts of chlorination : persistent organic pollutants (POPs)

When wool comes into contact with chlorine, a variety of chemical reactions take place, some of which lead to the creation of chlorinated organic compounds, aka organic compounds that contains one or more chlorine atoms attached to their carbon skeleton. The creation of such compounds is due to chlorine’s ability to substitute and oxidise products when it reacts with the proteins of the wool surface. Unfortunately, some of these chlorinated organic compounds are persistent organic pollutants (POPs), classified as such by the Stockholm convention.

For our purpose, we needn’t dvelve further into the organochemistry of chlorine. All we need to grasp is that persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are organic compounds that are resistant to degradation through chemical, biological, and photolytic processes. Simply put, persistent organic compounds are like super-durable trash that won’t easily break down. For instance, they can resist being broken down by natural processes like sunlight, water, and bacteria. This means that POPs can stick around in the environment for a long time, even decades or centuries. A well known example of such a persistent organic pollutant is dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). a chlorine-containing pesticides widely used in the 1940s and 1950s. This table below summarises the different health and environmental concerns associated with persistent organic pollutants (POPs), highlighting their potential adverse effects on human health and ecosystems worldwide.

| Persistence | Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are very resistant to breakdown, meaning that they can remain in the environment for decades or even centuries. This persistence makes it very difficult to clean up POP-contaminated sites. |

| Bioaccumulation | Bioaccumulation is the gradual accumulation of substances in an organism. Bioaccumulation occurs when an organism absorbs a substance faster than it can be lost or eliminated by catabolism and excretion. Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are lipophilic, meaning that they tend to accumulate in fatty tissues. This bioaccumulation can lead to toxic effects in both humans and animals. Bioaccumulation can also occur in the food chain. For example, fish that are contaminated with POPs can pass these contaminants on to humans who eat them. This is why pregnant women and young children are advised to avoid eating fish that are high in mercury, a POP. |

| Long range transport | Persistent organic pollutants can travel long distances through the air and water, becoming widely distributed throughout the environment. This can lead to exposureto POPs in remote areas far from the sources of pollution. |

| Adverse health effects | Exposure to persistent organic pollutants has been linked to a range of adverse health effects, including cancer, reproductive problems, immune system dysfunction, neurological disorders, and endocrine disruption. |

| Global impact | Persistant organic pollutants (POPs) are a global problem, affecting people and ecosystems in all parts of the world. This is because POPs can travel long distances through the air and water. For example, POPs that are released into the air in one country can travel to other countries and contaminate the environment. POPs pose a global threat. Highly polluting industries can (and often do) delocalise their activity to countries with less stringent environmental regulations, a lack of environemental regulations or a lack enforcement of their legislation. If these activities are delocalised, the pollution isn’t, it travels worldwide. In fact, the delocalisation of polluting industries not only contributes to the global spread of POPs but it also exacerbates the problem as the countries they relocate to often have fewer resources to manage and mitigate pollution. Untreated (or insufficiently treated) wastewaters, for instance, will cause ever-increasing POPs as the substances in the contaminated water will continue to chemically interact with each other, forming new and potentially more harmful compounds. This ongoing cycle of pollution and chemical transformation poses a serious threat to both human health and the environment. |

Adsorbable Organic Halides (AOX) : measuring the scale of the disaster

As R. Xu & al explain “adsorbable organic halogens (AOX)” is a comprehensive index defined as the sum of all halogenated organic compounds which can be adsorbed onto the activated carbon and detected by microcoulometry” (see here). In other terms, adsorbable organic halogens (AOX) are a measure of the total amount of organic compounds containing halogens (such as chlorine, bromine, or iodine) that can be attracted and held onto activated carbon. As we have seen, the chlorination of wool results in the creation of chlorinated organic compounds. These chlorinated organic compounds are a type of adsorbable organic halogen as they contain chlorine atoms, which have a strong affinity for activated carbon. AOX is a measure of the total amount of halogenated organic compounds in a sample. This measure allows industrials as well as public authorities to get an overall measure of how polluted water, soil, etc are.

Not all adsorbable organic halides are inherently harmful to the environment. Some occur naturally and ,pose no significant threat. Such compounds originate from various sources, including volcanic eruptions, marine organisms, and decaying plant matter. But though naturally occurring AOX compounds do exist, they are generally present in very low concentrations, can be used by living organisms and have few negative impacts for the environments. Unlike those synthetically created by human industrial activity that are at much higher concentrations and usually cause environmental pollution. Therefore the AOX measure remains a valuable tool for assessing overall pollution levels. Even if the AOX mesure doesn’t pinpoint specific harmful compounds, it gives us a broad idea of the overall presence of potential pollutants. Just like a fever tells us something’s wrong with our body, AOX tells us something’s (very) wrong with the environment.

The Hercosett process : a major source of AOXs

Agriculture, with its reliance on pesticides and insecticides, contributes to the production of synthetic AOXs. But the industrial sector also plays a significant role. Currently, the two industrial sectors causing the highest unintentional byproduct AOX contaminations are the pulp and paper industry on the one hand and the textile dyeing and finishing industry on the other. In the textile industry, several processes are known to contribute to the highest AOX pollution, including dyeing, the bleaching of cotton and…yes, the chlorination of wool ! Not all AOX created through the Hercosett process are caused by the chlorination of wool, but it is estimated that the chlorination of wool is responsible for between 50 % and 80 % of AOX generated in the process.

As Patagonia explains “Wastewater from the wool-chlorination process contains such high concentrations of chlorinated chemicals, that most wastewater treatment facilities in the United States do not accept it”. In fact, according to an information I found on the USDA website, the chlorination of wool is not authorised in the United States. Most (all ?) countries have set discharge limits of AOXs. Since the year 2000, the European restricts the acceptable concentraton to 0.5 mg/L for AOX wastewater discharges from sewage treatment plants.

Superwash and the pollution haven hypothesis: examining China’s role in the global wool industry

Australia, along with New Zealand, stands as the primary breeder of Merino wool, commanding together 80% of the global market share. However, a noteworthy aspect is that Australia predominantly exports its Merino wool as greasy wool,, without undergoing scouring or carbonization. For the period between July 2022 and July 2023, a staggering 95.6 % of Australian wool was exported in its greasy state.. China was Australian’s wool clip : China imported more than 82.5% of Australian wool by weight. Argentina , the third larger producer of merino wool, also exports part of its clip to China, predominantly as greasy wool too.

China’s dominance in the wool processing industry has been steadily increasing and nowadays, China plays a very significant role in the wool industry. China not only a major importer but also a significant sheep breeder, with a livestock count of 194 million sheep in 2022. Moreover, China has demonstrated ambitions in fine wool production, exemplified by the development of a new Merino breed, the Mountain Merino sheep, as announced in 2016 by the Chinese authorities. China is thus a major player in the global wool industry, processing its own wool as well as imports from other countries. China’s wool processing capabilities are extensive, encompassing various stages of processing, including scouring, carbonizing, dyeing, and spinning. China’s wool processing industry is characterized by its large scale, efficient production processes, and cost-competitiveness. As Woolmarks delicately puts it : “(…) Australia’s wool is exported, with the vast majority of this exported to China where it goes through the initial stages of its journey into becoming clothing“. In plain English, this means that the very polluting stages of processing merino wool – including the chlorination/Hercosett treatment – have been delocalised to China!

In 2022, amidst increased geopolitical tensions, the Australian wool industry started considering whether relocating in Australia about 50 % of the processing of its wool might be a good tactical move. The aim : reducing supply chain and trade risks.

WoolProducers Australia’s general manager Adam Dawes stated such a move would enable the Australian wool industry to “offer assurances around some of the credentials of some processing innovations — such as using renewable energy [and] decreased water consumption“, which in turn would “all add to the story of sustainability that is Australian wool“.

It would indeed! In this PR campaign, Dawes conveniently omitted a crucial detail: this partial relocation would primarily mean reducing the release of harmful AOXs into Chinese waterways. It would not mean that yarn mills in Australia would be authorised to treat their merino wool with the chlorination-Hercosett process as they used to. There is no way the Australian government would agree to the release of such high levels of synthetics AOxs into Australian waterways. There is also just no way that Australians citizens would agree to a sudden and massive increase of AOXs in their water in the name of superwash Merino being more “convenient” and the chlorination of wool being the cheapest and most efficient way to achieve this ! And you wouldn’t either, would you?

Partially relocating the shrink-proofing process to Australia would compel the industry to embrace more eco-friendly alternatives to the Hercosett method or advocate for the advantages of non-superwash merino wool. Currently, the outsourcing of wool chlorination in China allows the Australian wool industry – amongst others – to turn a blind eye to the environmental damages caused by relying on this outdated method for superwashing wool.

The pollution haven hypothesis posits that, when large industrialized nations seek to set up factories or offices abroad, they will often look for the cheapest option in terms of resources and labor that offers the land and material access they require. Developing nations with cheap resources and labor tend to have less stringent environmental regulations, and conversely, nations with stricter environmental regulations become more expensive for companies as a result of the costs associated with meeting these standards. I am not an economist and therefore in no position to provide you with an analysis on whether or not this hypothesis is relevant to the outsourcing of the superwash wool treatment in China. But what we do know is that China – and its waterways – are paying a high cost for the polluting industries it harbours. China’s water is highly polluted and this pollution has been found to exacerbate the already existing water scarcity woes.

Peristent organic pollutants don’t respect borders and water and air contamination will eventually find their way to distant places, including countries where more stringent environmental regulations are systematically enforced. But here’s the thing: when persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are detected far away from their source, as in the northern East China Sea, it becomes incredibly challenging to attribute responsibility for it.

Untreated (or insufficiently treated) wastewaters, will cause ever-increasing POPs as the substances in the contaminated water will continue to chemically interact with each other, forming new and potentially more harmful compounds. The global wool industry has chosen to persist in relying on a highly toxic industrial process to superwash wool – chlorination – and has chosen to outsource this process to China. As long as the Chinese communist regime remains in power, I will go as far as to stay that this is a clever move the global wool industry has put in place to cover its tracks. But let’s always keep in mind that while you can outsource an industrial process, persistent organic pollutants can’t be outsourced! Let’s not be fooled by their s the wool’s industry moke and mirrors, or buy into their greenwashing tactics. The damage lingers, no matter where they try to sweep it under the rug. Let’s not buy superwash wool. It’s bad for the environment, it’s bad for the animals, it’s bad for us and especially the people living near the plants that scour and superwash wool.

Flabbergasted

When I started writing this serie about superwash wool, I did it with the intent of uncovering the full environmental impact of this wool treatment. I was unimpressed by what I had read so far in knitting blogs as I found the information far too vague to my liking. So I started an in depth research. And as I am not a chemist, it proved difficult. So I used AI. I used AI like if I was a journalist and a source was telling me a story that I need to crossreference and verify. AI provided me with the keywords I needed to search articles and websites related to our current topic. That’s why I am not sure I have told you all that needs to be said about the impact of chlorination as it is still practiced to this day in the pre-chlorination/Hercosett process.

It’s taken me much more time to write this post as anticipated. Because I had not expected this level of toxicity and I wanted to make it extra sure I had gotten this right. Conclusion : there is 0% doubt that the chlorination of wool produces persistent organic pollutant and there is no way that future “refinements” of the chlorination process could avoid producing such pollutants. The only way to avoid the production of persistent organic pollutants is to create superwash wool that is not chlorinated. The good news is that such superwash wool already exists. There already are alternatives to the pre-chlorination/Hercosett process. If you buy superwash wool that is GOTS-certified, you are buying a wool that has not been chlorinated. GOTS forbids the chlorination of wool. As far as I know, it is the only one that does so.

To my dismay, none of the superwash wool I ever bought was GOTS-certified. And so part tof my handknitting hobby legacy are persistent organic pollutants! Needless to say, I am flabbergasted. Appalled. Mortified. And rather angry that yarn companies still use chlorination and that it is still allowed. At one point, I even starded doubting myself. Had a misunderstood something crucial ? Why did all these countries sign the Stockholm convention only to export/import superwash wool that has been chlorinated? And then I recalled that we live in a world were polyester accounted for 54 % of the fibres used in the textile industry in 2021, well before cotton (22 %). Polyester, a synthetic fibre that takes up to 200 years to decompose. Doubting my own ability to read English doesn’t make sense. What needs questioning is how come we know so little about the wool we buy and why the entire textile industry is polluting the environment instead of clothing us using all the wonderful natural fibres that are entirely biodegrable and durable. From now on, my knitting journey is based on me knitting my stash and scrutinising the yarn labels of any new purchase.

Next

I know this post is a long read. My target audience is fellow knitters, wool enthusiasts in general and fibre artists and crafters. It is my belief that if we are to make informed decisions as far as our yarn purchases are concerned, we need to understand the issue as best as we can. Therefore the length of this post. And I’m not even done yet! Let’s recall here that the chlorination of wool is just one of the steps of the Hercosett process. In further posts, we shall be discussing the superwash wool alternatives to the Hercosett process that already exist. We shall also continue following the full life cycle of superwash wool.

In the Hercosett process, wool that has been chlorinated requires additional chemical treatment before the resin coating can be applied. This step of the Hercosett process as well as the application of the resin coating will be the focus of my next post on this topic. As of yet, I don’t have all the documentation I need to write this post. I don’t know how long it will take me, but I don’t plan on working on it before January. Meanwhile, I shall still be posting unsolicited knitting advice on a regular basis.

References :

- Wikipedia, following articles : Chlorine, Persistent organic pollutant (POP) , DDT, Halogen, Cystein, Organochlorine chemistry, Stockholm convention on persistent organic pollutant, Adsorbable organic halides (AOX), Bioaccumulation, Pollution haven hypothesis, Pollution in China

- Mohammed Hassan, Christopher Carr : A review of the sustainable methods in imparting shrink resistance to wool fabrics. 2019. Journal of Advanced Research, Vol 18, p. 39-60. (read online – free access)

- Bettina Müller :Adsorbable organic halogens in textile effluents. Review of Progress in Coloration and Related Topics, 2008, vol 22, nr. 1, p. 14-21 (read online)

- Ja Rippon : Friction, felting and shrink-proofing of wool in Friction in textile materials, 2008 (pp. 253-291). Woodhead Publishing.

- https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/life/publicWebsite/project/LIFE05-ENV-D-000195/sustainable-aox-free-superwash-finishing-of-wool-tops-for-the-yarn-production (read online – free access). On this European Union website, there is a link where you can download a layman report titled “Layman´s Report zum EU LIFE III Projekt „SUPERWOOL, RICHTER Färberei und Ausrüstungs-GmbH”. Regrettably, this report is only available in German).

- Wong, Wen Jun. Acid red 1 dye absorption by wool found to not be heritable for wool pre-treated with a chlorination process. Diss. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries Western Australia) Dr. Tony Schlink (University of Western Australia) Dr. Andrew Thompson (Murdoch University) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for degree of Bachelor of Animal Science, Murdoch University, 2015. (read online-free access)

- Xu, R., Xie, Y., Tian, J., & Chen, L.: Adsorbable organic halogens in contaminated water environment: A review of sources and removal technologies, Journal of Cleaner Production, 2021, vol. 283, p. 124645. (read online)

- Toxicology of persistent organic pollutants (short information sheet, read online- free access)

- Hosam El-Sayed : The Current Status and Future Insight into the Production of Machine-washable Wool, Journal of Natural Fibers, 2022, volum 19, Nr .15, 10293-10305 (read online).

- EWG : 220 Million Americans Could Have Chloroform in Their Tap Water, september 8, 2017 (read online – free access)

- EWG : What is sodium hypochlorite, November 21, 2023 (read online- free access) ; this short article highlights the health dangers associated with sodium hypochlorite, an active ingredient in many household cleaning products ; I have nevertheless included this reference as sodium hypochlorite is widely used in the chlorination of wool. Sodium hypochorite is inexpensive and is an effective way to remove impurities and prepare the wool for dyeing or other treatments, such as the Hercosett process.

- World Health Organization : Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) – Children’s Health and the Environment : WHO Training Package for the Health sector (read online- free access)

- Ma, T., Sun, S., Fu, G. et al. Pollution exacerbates China’s water scarcity and its regional inequality. Nature Communications, 2020 11, 650 (read online – free access)

2 thoughts on “Knitting advice Nr. 11: Don’t buy superwash wool (part 3)”